This article was originally published on Muftah.org and has been reprinted here with permission.

http://muftah.org/blues-allah-power-cultural-symbols-across-borders/

Margaret Lanzetta is a New York based artist who has lived and worked in places as diverse as Morocco, Syria, India, and Japan. Inspired by these experiences, and using visual patterns of untraceable cultural origin, her work focuses on various themes, such as the place of religion in public space, the relativity and migration of cultural motifs and symbols, and broader processes of nationalism and identity formation in the Middle East and North Africa.

In her solo exhibition Blues for Allah at Heskin Contemporary in New York (October 23-December 13, 2014), Lanzetta explored these themes. The exhibition borrowed its title from the 1975 Grateful Dead album honoring Saudi Arabia’s progressive, democratically inclined monarch, King Faisal – also a Grateful Dead fan – who was murdered that same year.

Lanzetta’s work is driven by several questions: What makes a pattern move? How does it change as it migrates and circulates? Such questions have also been asked in the arena of political and social theory, from McCarthyist fears of the Soviet “domino effect” to analysts who have speculated on the spread of uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East since 2011.

When a protest slogan travels, something inevitably changes. The rhythm may stay the same, but the message often mutates. When emerging in a different environment and context, whether recorded and uploaded to the web, or played on television, images and information fragment. Visually, the camera offers a limited view and what escapes the zoomed-in frame may not circulate with the rest of the audio/visual material. But, on the edges, remnants of images may appear, along with sound bytes, including frayed bits of what came before and after.

Reflecting this phenomenon, Lanzetta works with patterns to fragment, slice, reconfigure, and reassemble them. Lanzetta generally silkscreens small units or sections of patterns repeatedly to create coherent, substantial, and ostensibly “whole” images, further emphasizing the process of fragmentation and re-assembling. In the process, new patterns create patched together “wholes” that speak to a global cacophony of cultures and religions.

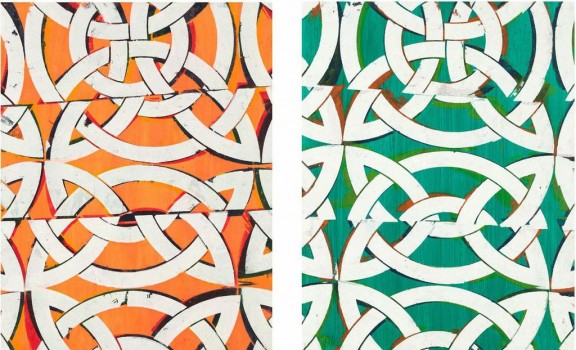

Left: Air Chrysalis, oil and acrylic on panel, 23 x 18″ 2014

During the opening of her show at Heskin Contemporary, a number of guests commented on the striking similarities between the gallery’s wrought iron window and the geometries in Lanzetta’s work. While the artist did not intend such a direct connection, the process of de-familiarizing the viewer, and subsequently re-familiarizing them within new perspectives, is integral to Lanzetta’s work.

Left: Sleaze Fame, oil and acrylic on panel, 20 x 16″ 2014; Right: Chance Directed, oil and acrylic on panel, 23 x 18″ 2014, Collection of Michel Beihn, Fes

To appreciate aesthetics at home, which for Lanzetta is New York, one often has to leave it behind. In this spirit, the artist spent 2012 living and painting in the old city of Fez, the largest and oldest medina in the world. She described the landscape as a “visceral sensation” of cultural and aesthetic convergence that left its mark on her practice. The labyrinthine medina, overwhelming in its density and the fragmented beauty of its architecture, revealed “colors and patterns consistently forming and re-forming, and symbols constantly shifting in and out of focus.” This context encouraged Lanzetta to query the meaning of globalization, nationalism, cultural identity, and fragmentation. The paintings in Blues For Allah were created as a reflection of this dialogue.

A View of Fes, Morocco

In Lanzetta’s visual interpretation, the medina’s confined environment is subconsciously articulated by more fragmented compositions. Patterns in built environments have long fascinated the artist. In Morocco, Lanzetta interpreted the confines and corners of the medina within a series of patterns, fragmented yet maintaining a sense of continuity. “The contiguous architecture in the medina and throughout Morocco, [which] highlights the old and traditional, is also practical in terms of living and building,” she says. These appearances of continuity contrast with broader socioeconomic conditions throughout North Africa such as the acute inequalities and other forms of social fragmentation seen through urban divisions, like that between Fez’s medina and the so-called Ville Nouvelle(the portion of urban Fez built during and since the French colonial period). In the artist’s visual interpretation, the broad streets and open plazas in the Ville Nouvelle clash with the occasionally claustrophobic, jagged edges of the medina’s alleys and unexpected corners.

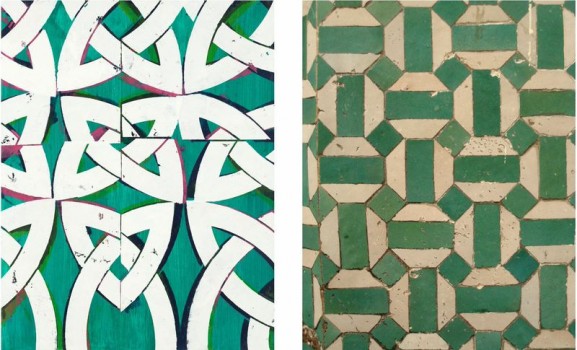

Left: Patrimony, oil and acrylic on panel, 23 x 18″ 2012 Right: Rein I, oil and acrylic on panel, 23 x 18″ 2012

Left: Photo of Les Jardins Majorelles in Marrakech, Right: Daydream Believer, oil and acrylic on panel, 12 x 12″

Lanzetta regards experimenting with and using color as essential to her creative process. Her working palate before Morocco focused on warm color schemes of magenta, yellow, and orange – intense hues chosen because of their spiritual significance in India and Japan. Her paintings in Morocco demonstrate a new shift towards blues and greens, which dominate Moroccan tile work and architecture. In paintings such as Blue Cheer and Tight End, one finds the periwinkle blues of the Moroccan mountain town, Chefchaouen, where the artist sought out local pigments from artisan painters. For Lanzetta,it is significant that the color green, long considered the traditional color of Islam, sits in harmonious conversation with the magentas, yellows, and oranges so redolent in Hinduism and Buddhist.

Left: Photo of Chefchaouen, Morocco; Right: Blue Cheer (Augustus Owsley Stanley III), oil and acrylic on panel, 23″ x 18″ 2013

Right: Inherited Capital

oil and acrylic on panel

23 x 18″ 2012; Left: Photo of tiles in Morocco

Right: Tight End, oil and acrylic on panel, 12 x 12″ 2012

Left: Code Switching

oil and acrylic on panel

23 x 18″ 2012

The repetition of aural and spiritual practices is also a pervasive theme in Lanzetta’s work. In Morocco, she found the repeating aural patterns marking daily life in the medina nearly as influential as the visual patterns. The scrap metal collector calling out as he walked block to block, the hammering of tinsmiths and “the daily call to prayer, starting at one end and reverberating from minaret to minaret across the medina” came together to create a rhythmic soundscape of patterns within which Lanzetta created her work.

Left: Hot, Slippery, acrylic on panel, 12 x 12″ 2012; Right: All City, acrylic on panel, 12 x 12″ 2012 , Collection of Nawal Slaoui, Casablanca

If there is a theory of change, circulation, and articulation in Lanzetta’s work, it may be found in this statement from the artist: “We all have a visual language inside of us and this can be used as a metaphor for cultural and social change…You can reassemble and refigure these patterns and symbols in different, more modern ways. Everything doesn’t have to be thrown out for change. You can reassemble and re-slice.”

Left: X Class, oil, acrylic on panel, 12″ x 12″ 2012; Right: Wall of Sound, oil, acrylic on panel, 12″ x 12″ 2012

Quarantine; oil and acrylic on panel; 12 x 12″ 2012

Many nation-states would do well to heed this advice. In Lanzetta’s work, there can be no pure, authentic culture form. “We are all the product of these hybrid cultures and ideas, especially in a place as rich and diverse as the Middle East and North Africa with so many societies based on tribes and autonomous groups,” says Lanzetta. Her comment hints at intensifying global trends, like nationalism and racial violence, brought about by a globalization that has created vast inequalities and nurtured state violence. But even as borders continue to proliferate, securitization and militarization increase, and xenophobia and crackdowns on immigration rise, people and patterns continue on. In this way, Lanzetta’s work helps us to de-familiarize ourselves inside our own borders, and re-familiarize ourselves outside of them.

Click on the image below to view an animated tour of the exhibit

Blues for Allah Exhibit; Heskin Contemporary, New York (October 23-December 13, 2014)