Please head over to the “Recent Publications” page!

Language Arts in Morocco: reflections on the new Mohammed VI Modern and Contemporary Art Museum and a conversation with translator Zakaria Alilech /

See my recent article for Kalimat Magazine's online Art + Design section. A sneak preview...

"In October, after a decade of construction, the Mohammed VI Modern and Contemporary Art Museum finally opened its doors to the public. Its first exhibition is a collection entitled, 1914-2014: 100 Years of Creation, and according to the museum’s official Facebook page, it garnered over 30,000 visitors within a month of opening. 1914, far from being an arbitrary antecedent to 100 years of creation, also marks the year the French Protectorate formalised its presence in Morocco. After having put down rebellions near Casablanca and Fez, postage stamps formerly bearing the label “Poste Français” were superimposed with a rubber stamping noting the “Protectorat Français....”

More Here: http://www.kalimatmagazine.com/artdesign/14092337

“Blues for Allah”: Artist Margaret Lanzetta’s Reflections on Patterns Across Time & Space /

This article was originally published on Muftah.org and has been reprinted here with permission.

http://muftah.org/blues-allah-power-cultural-symbols-across-borders/

Margaret Lanzetta is a New York based artist who has lived and worked in places as diverse as Morocco, Syria, India, and Japan. Inspired by these experiences, and using visual patterns of untraceable cultural origin, her work focuses on various themes, such as the place of religion in public space, the relativity and migration of cultural motifs and symbols, and broader processes of nationalism and identity formation in the Middle East and North Africa.

In her solo exhibition Blues for Allah at Heskin Contemporary in New York (October 23-December 13, 2014), Lanzetta explored these themes. The exhibition borrowed its title from the 1975 Grateful Dead album honoring Saudi Arabia’s progressive, democratically inclined monarch, King Faisal – also a Grateful Dead fan – who was murdered that same year.

Lanzetta’s work is driven by several questions: What makes a pattern move? How does it change as it migrates and circulates? Such questions have also been asked in the arena of political and social theory, from McCarthyist fears of the Soviet “domino effect” to analysts who have speculated on the spread of uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East since 2011.

When a protest slogan travels, something inevitably changes. The rhythm may stay the same, but the message often mutates. When emerging in a different environment and context, whether recorded and uploaded to the web, or played on television, images and information fragment. Visually, the camera offers a limited view and what escapes the zoomed-in frame may not circulate with the rest of the audio/visual material. But, on the edges, remnants of images may appear, along with sound bytes, including frayed bits of what came before and after.

Reflecting this phenomenon, Lanzetta works with patterns to fragment, slice, reconfigure, and reassemble them. Lanzetta generally silkscreens small units or sections of patterns repeatedly to create coherent, substantial, and ostensibly “whole” images, further emphasizing the process of fragmentation and re-assembling. In the process, new patterns create patched together “wholes” that speak to a global cacophony of cultures and religions.

Left: Air Chrysalis, oil and acrylic on panel, 23 x 18″ 2014

During the opening of her show at Heskin Contemporary, a number of guests commented on the striking similarities between the gallery’s wrought iron window and the geometries in Lanzetta’s work. While the artist did not intend such a direct connection, the process of de-familiarizing the viewer, and subsequently re-familiarizing them within new perspectives, is integral to Lanzetta’s work.

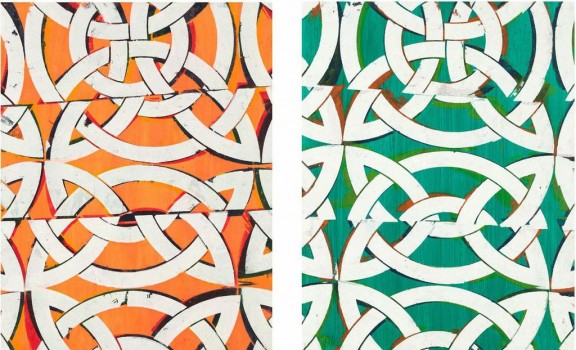

Left: Sleaze Fame, oil and acrylic on panel, 20 x 16″ 2014; Right: Chance Directed, oil and acrylic on panel, 23 x 18″ 2014, Collection of Michel Beihn, Fes

To appreciate aesthetics at home, which for Lanzetta is New York, one often has to leave it behind. In this spirit, the artist spent 2012 living and painting in the old city of Fez, the largest and oldest medina in the world. She described the landscape as a “visceral sensation” of cultural and aesthetic convergence that left its mark on her practice. The labyrinthine medina, overwhelming in its density and the fragmented beauty of its architecture, revealed “colors and patterns consistently forming and re-forming, and symbols constantly shifting in and out of focus.” This context encouraged Lanzetta to query the meaning of globalization, nationalism, cultural identity, and fragmentation. The paintings in Blues For Allah were created as a reflection of this dialogue.

A View of Fes, Morocco

In Lanzetta’s visual interpretation, the medina’s confined environment is subconsciously articulated by more fragmented compositions. Patterns in built environments have long fascinated the artist. In Morocco, Lanzetta interpreted the confines and corners of the medina within a series of patterns, fragmented yet maintaining a sense of continuity. “The contiguous architecture in the medina and throughout Morocco, [which] highlights the old and traditional, is also practical in terms of living and building,” she says. These appearances of continuity contrast with broader socioeconomic conditions throughout North Africa such as the acute inequalities and other forms of social fragmentation seen through urban divisions, like that between Fez’s medina and the so-called Ville Nouvelle(the portion of urban Fez built during and since the French colonial period). In the artist’s visual interpretation, the broad streets and open plazas in the Ville Nouvelle clash with the occasionally claustrophobic, jagged edges of the medina’s alleys and unexpected corners.

Left: Patrimony, oil and acrylic on panel, 23 x 18″ 2012 Right: Rein I, oil and acrylic on panel, 23 x 18″ 2012

Left: Photo of Les Jardins Majorelles in Marrakech, Right: Daydream Believer, oil and acrylic on panel, 12 x 12″

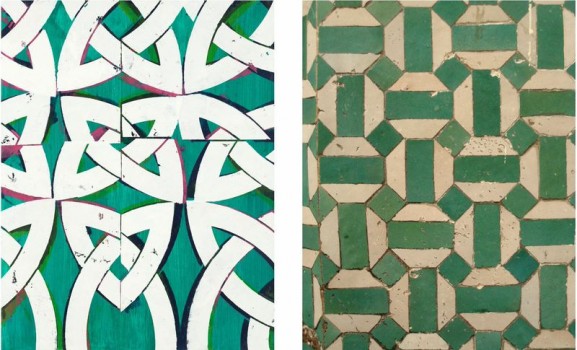

Lanzetta regards experimenting with and using color as essential to her creative process. Her working palate before Morocco focused on warm color schemes of magenta, yellow, and orange – intense hues chosen because of their spiritual significance in India and Japan. Her paintings in Morocco demonstrate a new shift towards blues and greens, which dominate Moroccan tile work and architecture. In paintings such as Blue Cheer and Tight End, one finds the periwinkle blues of the Moroccan mountain town, Chefchaouen, where the artist sought out local pigments from artisan painters. For Lanzetta,it is significant that the color green, long considered the traditional color of Islam, sits in harmonious conversation with the magentas, yellows, and oranges so redolent in Hinduism and Buddhist.

Left: Photo of Chefchaouen, Morocco; Right: Blue Cheer (Augustus Owsley Stanley III), oil and acrylic on panel, 23″ x 18″ 2013

Right: Inherited Capital

oil and acrylic on panel

23 x 18″ 2012; Left: Photo of tiles in Morocco

Right: Tight End, oil and acrylic on panel, 12 x 12″ 2012

Left: Code Switching

oil and acrylic on panel

23 x 18″ 2012

The repetition of aural and spiritual practices is also a pervasive theme in Lanzetta’s work. In Morocco, she found the repeating aural patterns marking daily life in the medina nearly as influential as the visual patterns. The scrap metal collector calling out as he walked block to block, the hammering of tinsmiths and “the daily call to prayer, starting at one end and reverberating from minaret to minaret across the medina” came together to create a rhythmic soundscape of patterns within which Lanzetta created her work.

Left: Hot, Slippery, acrylic on panel, 12 x 12″ 2012; Right: All City, acrylic on panel, 12 x 12″ 2012 , Collection of Nawal Slaoui, Casablanca

If there is a theory of change, circulation, and articulation in Lanzetta’s work, it may be found in this statement from the artist: “We all have a visual language inside of us and this can be used as a metaphor for cultural and social change…You can reassemble and refigure these patterns and symbols in different, more modern ways. Everything doesn’t have to be thrown out for change. You can reassemble and re-slice.”

Left: X Class, oil, acrylic on panel, 12″ x 12″ 2012; Right: Wall of Sound, oil, acrylic on panel, 12″ x 12″ 2012

Quarantine; oil and acrylic on panel; 12 x 12″ 2012

Many nation-states would do well to heed this advice. In Lanzetta’s work, there can be no pure, authentic culture form. “We are all the product of these hybrid cultures and ideas, especially in a place as rich and diverse as the Middle East and North Africa with so many societies based on tribes and autonomous groups,” says Lanzetta. Her comment hints at intensifying global trends, like nationalism and racial violence, brought about by a globalization that has created vast inequalities and nurtured state violence. But even as borders continue to proliferate, securitization and militarization increase, and xenophobia and crackdowns on immigration rise, people and patterns continue on. In this way, Lanzetta’s work helps us to de-familiarize ourselves inside our own borders, and re-familiarize ourselves outside of them.

Click on the image below to view an animated tour of the exhibit

Blues for Allah Exhibit; Heskin Contemporary, New York (October 23-December 13, 2014)

Algeria at a Crossroads: Borders and Security in North Africa /

This article was originally published on Muftah.org and has been reprinted here with permission.

http://muftah.org/algeria-crossroads-borders-security-north-africa/

The militarization of border crossings throughout North Africa and the Sahel has intensified recently, as a result of security concerns over weapons smuggling, terrorist networks, and armed violence in Libya. Algeria’s border lies at the center of many of these developments.

As of May 2014, Algeria has closed 6,385 km (3,967 miles) of its borders with Mauritania, Mali, Niger, and Libya, and placed its border crossings under military control. Algeria’s southern border with the Sahara is also incredibly vast and difficult to monitor. It has long been a major crossing for thousands of migrants from sub-Saharan Africa traveling through Agadez, Niger to the southern Algerian city of Tamanrasset.

It is in response to the decades of illegal smuggling and international calls to eliminate terrorist networks operating out of this relatively ungoverned “no-man’s land” that the Algerian government has now increased patrols and militarization of this border region. According to sources cited by Al-Monitor, “the army banned access to the desert corridors in the southeastern border region without a prior security permit. These measures will further tighten the noose around the neck of terrorist groups in desert pathways….these strict instructions will eliminate terrorism in the Algerian Sahara.” To the east, Algeria must manage a vast border with Libya, which has been nearly overtaken by armed militias that threaten to spill over into Tunisia, Algeria, and Egypt.

In light of these various threats to regional security, it is tempting to view the Algerian government’s actions as a direct consequence of militant activity. But, Algeria’s recent border closures represent more of a continuation, rather than a rupture, in its regional policies.

Algeria’s total closure of nearly all its borders (only the Tunisian frontier remains open) is a concerted effort to maintain and secure its economic and political relations with EU and NAFTA countries, at the expense of potential trade and, perhaps, long-term partnerships, with neighboring states. From the perspective of the Algerian government, this isolationist stance functions as a potential buffer against the uncertainty surrounding it.

It also parallels Algeria’s continuing border closure with its neighbor to the west, Morocco. Since 1994, Algeria’s border with Morocco has been officially closed. The Algerian government has historically had frosty relations with Morocco over issues ranging from drug smuggling to territorial conflict over the Western Sahara. The question of borders and territory represents a key area of contestation between Morocco and Algeria. An inability to cooperate on political matters not only plagues the two countries, but also rules out any hope for bilateral or regional economic integration through the Arab Maghreb Union (UMA), a regional institution founded by the leaders of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Mauritania in 1989, which sought to coordinate economic, political, and security issues through greater coordination between the five states of the greater Maghreb.

Monitoring the 1,559 km (969 miles)—or 1,601 km including the Western Sahara—borderline between the two countries has been difficult for the two regional rivals.

The recent border closures, and their intended consequences, are not isolated events. Rather, they are reflective of the Algerian government’s standing policies on dealing with the preexisting networks of trade, formal and informal, and trafficking that run through the country.

These three particular nodes of pressure give important context to Algeria’s recent border closures, and reveal the disconnect between the regime’s historical aims and the day-to-day circumstances of the Algerian people.

Point of Pressure 1: the Moroccan-Algerian Rivalry and the Western Sahara

The source of Moroccan-Algerian tension is often attributed to the Western Sahara conflict. After Spain left the territory in 1975, a dispute arose between two groups in the area. An indigenous movement known as the Polisario Front—which is fighting for independence and a referendum for self-determination—and the Moroccan government—which claims to have historical ties with the land—have clashed over the territory. The Moroccan government has proposed a regional autonomy plan for the Western Sahara, while Algeria has consistently backed the Polisario and supported a referendum for self-determination in the region.

But disputes between Algeria and Morocco pre-date the Western Sahara question, which became a regional preoccupation only in the 1970’s. While this conflict is an important obstacle to improving relations between the two countries and increasing the likelihood of regional economic integration—currently next to nonexistent—Yahia H. Zoubir, Professor of International Relations and Director of Research in Geopolitics at Euromed Management, argues that:

“Algerian-Moroccan relations have always been at odds, the existence since 1989 of the Arab Maghrib Union (UMA) notwithstanding. In fact, the UMA has not been operational due precisely to tensions between the two countries. Strained relations derive from a historical and post-colonial evolution – dominated by power politics – of which Western Sahara is only one, albeit major, aspect. Thus, a definitive resolution of the Western Sahara conflict will not necessarily mean a definitive ending of the distrust that exists between the two neighbours.”[1]

Following independence, Morocco and Algeria went to war over a border dispute that was left unresolved by France. The border war of 1963 was bloody and ended with a cease-fire in 1964 brokered by the Organization of African Unity (OAU). It was not until 1972, however, that the Moroccan-Algerian border was officially demarcated by a bilateral treaty. Algeria immediately signed the convention, which dealt with both border and economic cooperation, but Morocco did not officially recognize the agreement until 1989.

In 1988, diplomatic relations between the two countries were reestablished. 1989 marked the founding of the UMA. A UN brokered cease-fire in the Western Sahara finally took hold in 1991. Against this backdrop, the beginning of the 1990s was a hopeful time for regional relations and potential economic integration in the Maghreb.

Then, in August 1994, the Moroccan-Algerian border was officially closed, as a result of a“guerrilla attack” at the Atlas Asni Hotel in Marrakech, which Moroccan authorities believed Algeria had supported. After the incident, the Moroccan government deported thousands of Algerian tourists and official residents and applied new visa regulations to Algerians traveling to the country. In response, Algeria closed the border. Despite periods of warming relations between the two countries, the border has remained shut ever since.

The border closure implicates many issues, including the management of migration flows to Europe from sub-Saharan and North Africa, the existence of vast illegal drug smuggling as a result of Morocco’s approximately 57,000 hectares of cannabis production, and the increasing rise of armed terrorist groups, including Al-Qaeda in the Maghreb (AQIM). There are also concerns that, if the border was re-opened, Morocco would use it to pressure Algeria into withdrawing its support for the Polisario Movement.

While both countries have officially stated their desire to open borders and increase regional integration, the larger impact of such a move remains unclear, since the Arab Maghreb Union has not officially convened since 1994. Morocco and Algeria’s formal trade continues to be with EU countries, and “Trade within the AMU (UMA) quintet accounts for a paltry 2% of what the region conducts with the whole of the rest of the world.”

Point of Pressure 2: Formal and Informal Trade

Algeria’s formal trade networks virtually ignore its North African neighbors. According to data compiled by the MIT Observatory of Economic Complexity, Algerian exports of crude petroleum and petroleum gas make up 82% of its net exports. Refined petroleum (14%), and coal tar oil (1.2%) increase Algeria’s total mined exports to 97.2%, with the remainder of exports split among chemical exports and agricultural products. Most of these exports go to Italy (15%), the United States (15%), Spain (12%), France (7.5%), and Canada (7.4%). Algeria’s imports come from many of these same countries, in addition to China and Germany.

Like Algeria, Morocco’s import and export patterns also do not include its fellow North African countries. Only 1.3% of Morocco’s exports go to Algeria and 1.5% of Algeria’s exports go to Morocco. But forgoing regional trade relations comes with high opportunity costs. Over three billion dollars in Moroccan imports (8.45%) consist of crude petroleum, which comes primarily from Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Russia. With further instability in Iraq and potential economic sanctions on Russia, Algeria’s crude petroleum exports could find a home in its old rival.

Informally, smugglers on both sides of the Moroccan-Algerian border have a much friendlier relationship. There are no official statistics on how much hashish is exported by Moroccan traders via Algeria, nor how much medication and gasoline enter Morocco from Algeria. In 2013, however, The Guardian claimed the illicit gasoline trade generated income for 3,000 to 5,000 families in Morocco’s eastern province.

Algeria’s border crackdowns will surely have an impact on these long-standing informal trade relations. Measures taken by Morocco along the border will also have a negative effect on these networks. All in all, it is hard to tell which will have greater ramifications for these economic forces, Morocco’s proposed 450km long wall along the border or Algeria’s envisioned 700km long trench.

Point of Pressure 3: Migration

One of the primary routes into Europe from North Africa begins in the Nigerien city of Agadez, continues through southern Algeria, and goes up toward the coast. From there, many migrants follow the road west toward Maghnia, Algeria, and cross from Maghnia directly into Morocco, near the city of Oujda.

EU pressure to stop the flow of migrants from North Africa into Europe, combined with a seeming lack of cooperation between Algeria and Morocco, have resulted in more and more migrants being shuffled back and forth between the two countries with an alarming disregard for human rights.

On its eastern border, Algeria is dealing with a stream of migrants and refugees from Syria, Libya, Egypt, and Eastern Africa. As a result of these increased pressures, the Algerian government has pursued what appear to be contradictory policies. In mid-August, Algeria announced it would open portions of the border with Libya to facilitate the return of refugees from Egypt. Just a few days later, the government arrested 300 Syrians heading for the same Libyan border. It remains to be seen how these policies will play out.

Public Response

While Algeria’s borders continue to be the subject of domestic political debate, it is important not to conflate this conversation with popular consensus on the issue. Despite the closed borders, Algerians are able to travel to neighboring countries via air or by entering through another country. In August, the Algerian paper L’Expressionreported that the top four tourism destinations for Algerians were Turkey, Tunisia, Morocco, and Spain. Both Royal Air Maroc and Air Algiers offer regular flights between Algiers and Casablanca, though the cost is often prohibitive for residents looking to see family just across the border. The price of air travel, coupled with the time the journey requires, drives many families to make other arrangements.

One group of Algerian and Moroccan youth is following the example of residents of Naco, Mexico and Naco, United States, and arranging a cross-border volleyball match in October. Their aim is to draw attention to the individuals and families impacted by two decades of closed borders, and inspire dialogue focused on these affected people, instead of government political posturing.

Colonialisms’ Continuing Legacy

Ultimately, it is impossible to separate North Africa’s current borders from the recent history of European colonialism. While lines drawn on a map by colonial cartographers mean very little to the region’s social fabric or the lives of residents on either side of these borders, they have a strong impact on both. In the period following independence, Algeria and Morocco embarked upon parallel, but ultimately divergent, paths toward post-independence reformation. Morocco embraced its favored status with NATO and its member countries as a “model” for slow-paced reform after King Mohammed VI’s muchlauded constitutional reforms in 2011. Although many have criticized these reforms as strictly cosmetic, others have declared the measures as appropriate and reflective of Morocco’s history as a kingdom invested in tolerance and civil society.

At least rhetorically, Algeria has been a bastion of support for resistance and anti-imperialist movements. In contrast to its neighbor, Algeria pursued a largely socialist system until economic problems and political pressure caused it to accept IMF loans and economic restructuring in 1989. The country’s traumatic experience during the Black Decade of the 1990s, a period of great bloodshed fueled by armed conflict between government forces and militant Islamist groups, has remained in the backdrop, as the government watches instability in neighboring Libya and Mali unfold.

All in all, Algeria’s border closures are a function of its isolationist stance vis-à-vis regional neighbors, as well as the government’s efforts to keep out any potentially destabilizing external forces. This issue is not just about regional and domestic security for Algerian authorities, but also inherently connected to regime survival.

[1]Yahia H. Zoubir (2000) Algerian‐Moroccan relations and their impact on Maghribi integration, The Journal of North African Studies, 5:3, 43-74, DOI: 10.1080/13629380008718403

/

Wool washing between Ain Lleuh and Mrirt, Morocco.

/

Ain Alleuh, Morocco, and the train to Fez. I promise we aren’t shooting a western.

/

Day 2 of shooting in Khemiset.

/

Day 2 of shooting in Khemiset.

/

Help support The Magic Carpet: http://3arts.org/projects/magic-carpet-story-music/

The Magic Carpet is a new work produced by Borderline Theatre Company—a mobile, transnational theatre collective of which I am co-founder and artistic director. We develop new works based on classic stories, myths, legends and oral traditions, and center them around contemporary border conflicts. During my research along the Spanish-Moroccan and Moroccan-Algerian borders, it became clear that the story of star-crossed lovers held particular resonance in this region. Our lives are full of borders, from those that exist between Chicago neighborhoods to the military outposts between Morocco and Algeria. Through storytelling, I aim to uncover and share our common struggles, and our common joys, with people across the world.

While in Morocco as a Fulbright grantee, I came across a rug made with Moroccan patterns, but with Algerian colors. The merchant had no idea from where it came, but that it was something of an anomaly. Traditionally, the bottom of the rug is left open, so that stories and messages can be woven into the bottom of the rug, as time goes on. I brought this rug back to Chicago with me and now this rug is the framing device for our production. Using recorded oral histories from residents of the Moroccan border city of Oujda, I am using my research to develop The Magic Carpet, a new version of the world’s most tragic love story set along the Moroccan-Algerian border.

With the support of 3AP, I hope to produce a staged reading of this piece in late May. Following the reading, and the script workshop process that would accompany it, I plan to return to Morocco in June to conduct a free admission workshop reading of the piece in Oujda, the largest Moroccan city on the Algerian border. The funds I am raising will allow me to pay all of the artists involved with the project a modest stipend, rent the spaces needed, purchase props, and hire a videographer to capture both productions.

Chicago Artists Resource feature on grant-writing for artists /

Granted: George Bajalia

When we approached DCASE about recommending a candidate for a successful theater-oriented grant recipient, Director of Cultural Grants Allyson Esposito responded with two words: George Bajalia. Bajalia’s pitch for the Individual Artist Grant in 2013 was for research funding to travel to the frontier of Morocco and Algeria. There, he would gather materials to produce a high-quality play that showcased those cultures to a Chicago audience.Bajalia is interested in raising awareness through accessible storytelling, focusing on the geopolitical realities of people and the arbitrary borders that define or confine them.

Bajalia won $4,000 to research and produce The Magic Carpet. CAR corresponded with him via email to learn a bit more about how he pitched this successful endeavor to the City. His actual grant application documents are attached to the end of this article.

George Bajalia’s Approach:

Grantors want to fund our projects. They work in the non-profit, educational and civil sectors for a reason. They are actively trying to give financial support for artists, and that’s important to remember. Grantors are trying to help.

I start “free-writing” as soon as I find out about the grant. I ask myself why I want to apply for the grant. What project comes to mind? Why would that project be important to the grantor? For the Individual Artist Programgrant, I read through the prompts to get a sense for whom the funder was, and how the grant fit into to its mission. I didn’t worry about matching my responses to the prompts—or even what I wrote—as long as I got my thoughts down.

Grantors are really looking for someone with a clear vision who can articulate that vision to an outside audience.

This early stage is crucial; it’s when I write my most honest argument for why my work is a good fit for the grant. This writing is more candid than later drafts, but it is important. As I revise my writing, I try to distill the grant application into two questions: “Why is my work right for the grant?”and “Why am I the right person to carry it out?” Sometimes, I also answer the question, “Why right now,” though that answer often becomes evident in the editing process.

Affording myself the time to free-write responses is one of the primary advantages of starting early. Later, during the editing process, this work frees up time to hone my responses to address the prompts in an articulate manner.

Previously, when I applied for a Fulbright grant, I received some very good counsel: Fulbright isn’t always looking for good research, they are looking for good researchers. Grantors are really looking for someone with a clear vision who can articulate that vision to an outside audience.

I have to confess that I don’t always start early. The other good thing about the free-write is that I usually generate much more material than I need. A small amount of it is relevant. I never delete the excess; I compile it in a separate document. This material isn’t necessarily bad, it just may not be right for the proposal at hand. For ongoing projects, it can be really helpful to have this material as starting points for additional applications.

Demonstrate the ability to develop a realistic and executable plan.

Occasionally I’ll solicit the opinion of other directors and writers, but oftentimes I seek out the opinions of colleagues who work in other fields of the arts. Their critiques help me build a sense of the common vocabulary I should use for the proposal. Grant readers are individuals who have in-depth, but extremely varied, experiences with the arts. My proposal to fund a play needs to click with people from a diverse array of backgrounds. Getting feedback from fellow artists and arts administrators gives me a sense of what language is intelligible across backgrounds. It also provides extremely useful insight into how my project plan sits with potential audience members and collaborators.

George’s application had an incredibly clear writing style without sounding overly academic or abstract.

The most appealing thing to grantors is that you demonstrate the ability to develop a realistic and executable plan. Get specific about your plans for the grant’s support. Even if your final product ends up a bit different, these plans show that you have a well-defined framework. Any funds raised advance the project. At the end of the day, the grantor wants to fund somebody. We just need to help them believe in our work as much we do.

Allyson Esposito, director of cultural grants, DCASE:

George’s application had an incredibly clear writing style, conveying the potential and importance of his idea in high level concepts without sounding overly academic or abstract. He is focused on the development of a new work that has an exciting international component. Based on the artist’s work sample, the panel had every confidence that the final product will be involving, multicultural and open up dialogue around arbitrary borders. The premise of exploring arbitrary borders through the tangible metaphor of an incomplete rug is rich in both thematic and visual potential. Exceptionally detailed and accurate budget.

George Bajalia is a Chicago-based theatre artist and cultural critic. His research interests lie at the intersection of cultural globalization, identity performance and transnationalism within the Mediterranean region. Previously he was a Fulbright scholar in Morocco, where he adapted and directed a Moroccan Arabic production of West Side Story in addition to continuing research on the role of performance, on stage and off, in public discourse.

Bajalia is co-founder and artistic director of a transnational mobile arts lab called the Borderline Theatre Project, and is working with the Chicagotheatre company Silk Road Rising on a short film entitled Multi Meets Poly; Multiculturalism and Polyculturalism Go on a First Date. He is also working on his new play, The Magic Carpet, which examines the militarization of the border between Morocco and Algeria and the economies of exchange, both formal and informal, between residents on either side of the border.

Bajalia holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in communication studies and Mediterranean culture and history from Northwestern University. he is a staff writer for online magazine Muftah.org and a contributor to visual anthropology blog Signs of Seeing.

George Bajalia is also featured on the 3Arts website.

George Bajalia

/

This piece was originally published by Signs of Seeing.

http://signsofseeing.wordpress.com/2013/10/23/hyphen-views-from-the-moroccan-algerian-border/

Video link: http://vimeo.com/77474467

North Africa and Southern Europe are divided by a sea, a wide sea, yes, but a sea that for many centuries was little more than a river. Families lived on either side, and still do. Now, however, their movements are governed by national and international bodies with whom they have little relation. Along the eastern edge of Morocco, along the border between Morocco and Algeria, the discrepancy between colonially imposed borders and the people who they separate is pronounced. On the Moroccan side, people wait with knapsacks to unload the cut-rate cigarettes and medicines smuggled in from Algeria. Just outside of Saidia, people stop on the side of the road to wave across a ditch. In Saidia proper, poles and rope demarcate the border on the beach, and military keep watch to make sure that no one crosses in international waters.

In this video, I document a journey down to Figuig to Saidia, and back to Tangier. Taking the ferry from Tangier to Algericas, I crossed from Moroccan waters, into international waters, and into Spanish territory all within 45 minutes. I spent the majority of that time looking back towards Tangier, a white city on a hill, a city I had called home for nearly two years. Just a few short days earlier, I had crossed from Nador into Melilla, a Spanish enclave nestled on Morocco’s coast. A few days later, I would be crossing from La Linéa de Concepcion, Spain into Gibraltar, United Kingdom, and flying out from Gibraltar to London. At the outset of this journey, 2 continents, 3 countries, I spent my time on the ferry looking back. As I looked around me, however, I saw that I was one of the few people gazing back. Most people on the boat, whether business regulars or first time travelers to Spain, were looking forwards. They were looking out to the next step, snapping photos and recording videos of what was to come.

During my time in Tangier, I looked out across the Straits of Gibraltar to Spain and tried to understand how my friends who grew up gazing out across this sea possibly felt about my own travels. I was embarrassed about the privilege I held just by nature of my birth. Tangier was, for me, a nodal point; a point from which I was able to see the world, take ferries to planes to trains to buses and arrive again, safely at the intersection of the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. During these years, marked by coming and going from a city with porous borders and a strong informal economy, I came to realize that the passport I carry is the most valuable thing I have, and it doesn’t even belong to me. Driving from Figuig, in the southeast corner of Morocco, to Saidia, in its northeast corner, I carried it in my front pocket. I entertained some fantasy that I would be able to cross the border at some point, as long I had those helpful papers. It was a fantasy and nothing more. And I understood a little bit. Still no answers, but I’m closer to asking the right questions.

Algeria: Politics & Regional Power /

This article was originally published on Muftah.org and has been reprinted here with permission.

http://muftah.org/algerias-political-transitions-regional-power/

[Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika (Photo credit: Reuters)]

George Bajalia, with contributions from Toshiro Baum

Note: this article is the third in a series focusing on nationalism, human rights, and regional politics in Morocco, Algeria, and the Western Sahara. The previous piece in this compilation can be found here. A brief historical timeline about the conflict has also been created.

Protest, Power, and Regional Security

As popular uprisings rocked North Africa in 2011, protesters in Algeria took to the streets calling for government reforms. Unlike the uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, demonstrators in Algeria focused almost exclusively on economic issues rather than regime change. The protests were strongly supported by Algeria’s youth, and highlighted popular frustration with prevailing conditions as well as the regime’s weaknesses. The latter included the advanced age of many government leaders and the common perception they neither comprehended nor represented the concerns of the increasingly marginalized youth. Last May during a speech in the city of Setif, seventy-six year old Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika acknowledged this disconnect admitting that “for us [my generation] it is over,” and declaring the need for a new generation of leaders to take power.

While Algeria may finally be preparing for a transition in leadership, new political faces will not necessarily result in reforms to the regime’s underlying authoritarian and rentier frameworks. As Algeria’s aging leaders pass on the reins of political and economic structures—ranked as some of the most opaque and corrupt in the world—they will work to ensure any domestic push for structural reform does not receive international support. To achieve this, the regime will seek to further entrench Algeria as a key regional security partner for western powers, insisting that its political stability is necessary to counteract emerging terrorist and criminal threats in North Africa, the Sahara, and Sahel. In taking such a position, the regime will claim stability, rather than reform, should be the focus of international interest.

The Algerian state’s policies towards the Western Sahara can only be understood within the context of this aging regime and its dominance of the political landscape. For President Bouteflika and his supporters, Algerian politics has historically been subject two “diametrically opposed [ideological] poles:” democratization, which has led to ‘Islamization,’ and stability. The Bouteflika regime, as well as predecessor governments that ruled during Algeria’s civil war, have demonstrated their commitment to stability at the expense of democracy. In order to garner international support and bring stability to Algeria, the state has pursued a policy of supporting proxy groups in the larger Sahara and Sahel regions, particularly in the Western Sahara.

To ensure its position as the prime security partner in the Maghreb, the Algerian regime is likely to continue its support for regional proxy groups as a relatively cheap and effective method for projecting power into the seemingly ungovernable trans-Saharan territories. Algeria’s support for the Frente POLISARIO movement in the Western Sahara forms a key pillar of this strategy. Since 1973, the Frente POLISARIO has claimed to represent the Saharawi people in their fight for independence from Morocco.

The POLISARIO’s explicit focus on regional territorial disputes, rejection of transnational terrorism, and long-term dependence on Algerian support make it an ideal candidate through which Algeria can manage the Western Sahara’s persistent instability. This relationship ensures, in turn, that Algeria maintains its status as a necessary security partner for the international community, and staves off outside support for domestic reforms, which the Algerian regime views as necessary piece to its domestic and international security.

The Risk of a New Leadership Transition

Long-serving political leaders and single-party dominance are the norm in Algerian politics. From independence in 1962 until the late 1980s, the socialist National Liberation Front (FLN) presided over a one-party state. Since 1962, Algeria has only had five presidents. Of these, two were deposed by the military, one died in office, and the other resigned. Algeria’s current leaders—many of whom fought in the struggle for independence in the 1950s—are preparing to hand over power to a younger generation of leaders, more out of necessity than anything else. Old age and ill health means that few leaders from the independence era can continue in the country’s highest offices.

Current president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, took office in 1999 and is nearing the end of his third term. During the summer of 2013, he was hospitalized in France following a stroke and once again returned to the country for further treatment in January 2014. Despite his age and fragile health, Bouteflika is widely expected to win a fourth presidential term in elections to be held in April of this year. Many believe he will transfer power to a successor—or pass away—before his fourth term ends.

While a handover to a younger, more dynamic group of leaders would help the regime connect with an increasingly disenfranchised youth population, any political transition carries the potential for destabilization and unrest. Popular discontent in Algeria has so far been limited, but internecine fighting among regime elites has the potential to drive official corruption and abuses of power into the national spotlight. Combined with domestic and international calls for greater transparency and accountability, this attention could turn low-level popular discontent into a potent challenge to the regime’s stability.

Fear of the Return of the Black Decade

For Algeria, this possibility became an ugly reality in the early 1990s in a decade long civil war known as the “Black Decade.” In December 1991, the Front of Islamic Salvation (FIS), a coalition of Algerian Islamist Parties, won a resounding victory in elections for municipal councils and mayorships.

Invoking fears that an Islamist victory would lead to an Islamic theocracy, Algeria’s military leaders forced the government to suspend then-upcoming elections for national parliament. Popular belief held that the general’s chief concern was not an emerging theocracy but potential investigation into their corrupt dealings. Soon enough, protesters had taken to the streets. Security forces heavily repressed these demonstrations. Within a few months, the government declared a state of emergency while radicalized Islamist supporters launched an armed insurgency against the state. The civil conflict that followed would kill hundreds of thousands of Algerians and displace countless more. Tellingly, two of Algeria’s main international partners, the United States and France, did not denounce militar repression in the early years of the civil war, demand military leaders respect the FIS’ electoral victory, or use their permanent seats in the UN Security Council to pursue international sanctions against the Algerian regime.

As a new generation inherits the regime’s authoritarian structures, the potential for internal power struggles, challenges by domestic opposition groups, or even popular discontent at the continuation of “business as usual” will greatly increase. Fearing a return of the Black Decade (a fear which has only been exacerbated by the Arab Awakening) the Algerian regime has leveraged its new international position as a regional security partner to foreign governments and corporations concerned with their own interests to gain international support for its suppression of domestic challenges and threats. By casting its authoritarian structure as necessary to the preservation of both domestic and regional security, the regime has sought to ensure the tacit support of key international partners should it need to emulate the repressive crackdown of the early 90s.

The President and lePouvoir

Bouteflika came to power based on a platform of general amnesty and national reconciliation after the Black Decade. A longtime proponent of market reform and rapprochement with the West, Bouteflika’s ascension to the presidency reflected a desire among some Algerian powerbrokers to end the country’s long isolation after years of domestic conflict and the collapse of its former patron, the USSR. Known popularly as le Pouvoir, or the “power,” this elite group and its political and economic fortunes are inextricably linked to the shadowy regime.

Upon becoming president, Bouteflika worked quickly to improve Algeria’s foreign relations, which included making new inroads into Africa through the African Union and expanding economic investment in West Africa. The September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks and launch of an American-led “war on terror” gave Algeria the unexpected opportunity to recast its Black Decade as a fight against domestic Islamic terrorists and thereby improve its standing with Western powers, such as France, Spain, and the United States. To fortify these relationships, Algeria positioned itself as a regional security partner, and signed a strategic partnership agreement with the United States.

The POLISARIO, the Western Sahara, and Proxy Power

For Algeria, the Western Sahara has always been linked to a greater struggle. The country’s decade-long fight for independence from France, which began in the 1950s, helped to cement a national narrative and orient the personal worldviews of its early leaders toward fierce support for anti-colonial independence struggles. The 1963 Sand War—the military invasion of the newly independent Algeria launched by Moroccan King Hassan II—added to the regime’s fears. While King Hassan II claimed his actions were aimed at recovering historical Moroccan territory illegally given to Algeria by France, his irredentism presented a real threat to the new Algerian nation.

Algeria based its early support for the POLISARIO on two ideological principles: solidarity with the struggle for self-determination by inhabitants of the Western Sahara and a desire to undermine Morocco’s regional expansion-by-annexation policy. With the 1991 ceasefire between Morocco and the POLISARIO, Algeria began a concerted initiative to become the movement’s primary political backer. Throughout the 1990s, Algeria and POLISARIO politicians, matched by their equally obstructionist Moroccan counterparts, maneuvered to bring a UN-proposed referendum on Western Sahara independence to an inconsequential stalemate. By bringing this process to a halt, these parties were able to limit international influence in the region exclusively to indirect actions undertaken by non-governmental human rights organizations.

Over the last ten years, however, Algeria’s support for the POLISARIO has become part of a strategy for projecting its power into the Sahara and competing for regional dominance. Morocco’s efforts and substantial investment in securing the Western Sahara through direct military control helped prompt Algeria to move beyond the POLISARIO and co-opt armed groups in the region. Through this policy, Algeria has obtained effective and cheap, although not always certain,control over the vast and hard-to-secure expanse stretching across its southern borders, from Mauritania to Mali. Algeria’s proxy relationships give the regime crucial intelligence on the licit and illicit activities of groups operating in the Sahara – ranging from trade, terrorist training, and armed insurrection. Armed with this intelligence, the Algerian regime is uniquely placed to influence the behavior of actors within the Sahara and thus impact the complex relations that govern the region’s security.

Regional Security and the Prospects for Regime Change

As authoritarian regimes in Tunisia and Libya collapsed in 2011, maintaining security in the Sahara and Sahel became paramount for countries like Morocco and Algeria. The July 2012 coup and ensuing civil war in Mali illustrated the potentially destabilizing effects of the North African uprisings across the Sahara. For the European Union and United States, the rise of a jihadist statelet in Northern Mali confirmed the fear that ungoverned spaces, such as the Western Sahara, could allow radical Islamic terrorists to operate with impunity.

For international policy makers, the civil war in Mali vindicated Algeria’s adherence to supporting proxies in the Sahara. For example, the Movement for the National Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), an armed group claiming to fight for an independent Tuareg state in North Africa, became one of Algeria’s main partners in working to defuse and resolve the conflict in Mali. In 2012 the MNLA, along with other armed groups, captured the northern third of Mali. The MNLA eventually helped Algeria recover several diplomats taken hostage by a radical Islamist group in the Malian city of Gao. In a seeming about-face, the MNLA even turned on its former radical Islamist allies, assisted French troops in an intervention supported by Algeria, and became the main interlocutor in the ceasefire agreement between the Malian government and rebels endorsed by Algeria.

Conclusion

The Western Sahara issue has always played a key role in the Algerian regime’s foreign policy calculations. While Algerian support for the POLISARIO emerged initially from a sense of ideological solidarity with a post-colonial struggle, the opportunity to contain an aggressive neighbor quickly made the POLISARIO a useful tool of asymmetric foreign policy. Further inflaming and drawing attention to the Western Sahara issue remains a key piece of this strategy.

Bouteflika’s latest salvo, calling for the expansion of the UN Mission for a Referendum in the Western Sahara’s (known by its French acronym, MINURSO) mandate to include human rights monitoring, tarnishes Morocco’s human rights reputation and casts the kingdom as a threat to regional stability. Recently, the UN has charged MINURSO with enforcing a cease-fire agreement in the Western Sahara, in addition to preparing for a popular referendum on independence.

Bouteflika’s statement, delivered at a pan-African conference organized in the capital of Algeria’s ally Nigeria, carried significant undertones: Algeria, and not Morocco, should be the dominant diplomatic and political player in North and West Africa. The move is hardly accidental. Over the years, Algeria’s goals have evolved from protecting its borders from Moroccan incursions to preserving its position as a regional security partner to the West. In this regard, Morocco is Algeria’s main competitor for American and European Union partnership.

President Bouteflika’s unspoken message to the region and the international community is that Algeria, and Algeria alone, has the power to draw lines in the Sahara’s shifting sands and keep them from being crossed. With looming presidential elections and an inevitable transfer of political power in the country, ensuring the regime’s stability is key to maintaining its international position as well as preserving le Pouvoir. For the time being, the durability of Algeria’s autocracy rests in part on its use of the POLISARIO both to contain and preoccupy Morocco, and present itself as the only guarantor of security in a region where many European and American policymakers view stability as a top foreign policy priority.

*George Bajalia is a staff writer for Muftah and former Fulbright research grantee in Morocco. Follow him on Twitter @ageorgeb or at www.georgebajalia.com. Toshiro Baum is a former Fulbright research grantee in Morocco. Follow him on Twitter @toshirobaum.

Language, Theatre & Morocco’s February 20th Movement /

This article was originally published in Muftah.org and has been reprinted here with permission.

http://muftah.org/language-theatre-moroccos-february-20th-movement/

[Fatima El Zohra Lahouitar and Mouna Rmiki performing in the author’s piece F7ali, F7alek/Like Me, Like You in Tangier, Morocco. (Photo credit: Omar Chennafi)]

Morocco’s King Mohammed VI has successfully maintained a reputation for being a business-friendly, reform minded monarch, despite the wave of unrest that spread across North Africa in early 2011. The country’s February 20 Movement, also know as Feb20, which emerged at that time, called for “an end to autocracy and … corruption.” Since then, the king has taken advantage of positive international media attention to showcase Morocco’s comparative potential as a commercial hub and access point for new African markets. Quick cosmetic reforms to the constitution, followed by new parliamentary elections in November 2011, further solidified King Mohammed VI’s progressive image.

Despite a seeming decline in revolutionary sentiment in Morocco, the performing arts community has assumed new importance as an extension and continuation of the February 20 Movement’s ethos and objectives. Certain theatre groups in the country maintain Feb20’s ideological goals, and address themes of governance, reform, and secular politics in their work. But, even more important is the changing linguistic landscape of performance art in the country. Today many young performing artists in Morocco are, quite literally, altering the language for sharing and communicating their experiences. The usage of formal Modern Standard Arabic and French— traditionally the languages of high theatre in Morocco—has given way to more performances written and staged in conversational Moroccan Arabic.

This is symbolic on a number of levels. Darija is an ever-changing dialectical mix of Arabic, French, Amazight, Spanish, and English. Many Moroccans only learn Modern Standard Arabic, which bears little resemblance to the local vernacular, in school. As such, by using Moroccan Arabic in their performances, artists are signaling an overt shift in their focus. Instead of seeking out artistic conversations with cultural elites, these theatre practitioners are actively looking for audiences among the general public.

Moroccan Theatre in Context

Prior to Morocco’s independence from France and continuing into the King Hassan II era, Moroccan theatre acted as an outlet for spreading dissident messages. Low literacy rates and the prominence of storytelling traditions, such as halqa, made theatre into a tool for activating public discourse. In response, the state took an increasingly hands-on approach to theatre and established university festivals and municipal theaters. This encouraged the development of dramatic studies, while also offering government institutions the opportunity to regulate the types of performances taking place across the country. The dissident theatre of the early independence era was all but extinguished, and theatre became an emblem of high art, with performers and writers primarily using Classical Arabic or French.

Today, the linguistic landscape of Morocco’s official performing arts scene reflects this effort to control theatre discourse, especially at the many government-produced theatre festivals held in partnership with drama and performance studies departments at public universities. Although there is a great deal of progressive work happening within such festivals, audience members come mostly from among fellow theatre producers, academics, and critics, and not from the general public.

Since 2011, a new kind of theatre has taken hold in Morocco. A younger generation of artists, distinct from those who dominated the scene through the later part of King Hassan II’s rule, have started to form and lead theatre groups. Performance troupes such as DabaTeatr, Spectacle Pour Tout, Daha Wassa, and Theatre Aquarium favor a theatrical form called “devising.” Unlike standard script-based performances, “devising” is an improvised form of theatre where the text is developed in cast rehearsals, and then performed by the same group. Such performances use mixes of Moroccan Arabic, Amazight, French, and Classical Arabic, with codeswitching occurring constantly, based on cultural context and dramatic intention.

Unlike their more formal, state-sanctioned counterparts, these groups enjoy audiences that hail from across Morocco’s social and political spectrum. Because their language is less formal, these performances are accessible to all members of the public regardless of education level. That is to say, while not everyone understands everything, everyone understands something.

Besides their symbolic deployment of language, many of these new theatre pieces take up issues publicly championed by the February 20 Movement, as well as hot-button issues like sex tourism, secular politics, religious freedom, and freedom of the press. Often these are the same issues that cause controversy in the Moroccan press and have resulted in government crackdowns on independent publishers such as Ali Anouzla of Lakom.com and former Tel Quel and Nichane editor Driss Ksikes.

Theatre Group Profile: DabaTeatr

Driss Ksikes in particular has been instrumental in converting Morocco’s February 20 Movement into artistic creations. As a playwright, he has tackled subjects such as sexual repression and child abuse in Morocco. Both as a playwright and publisher of news-journal Nichane, Ksikes has strived to provide an outlet for Moroccan Arabic discourses. Since Nichane closed down in 2010 after being banned by the government, Ksikes has channeled his impulse for Moroccan Arabic-centric art and literature into the theatre company, DabaTeatr.

DabaTeatr began in 2004 under the direction of Jaouad Essaouni, an artist and mentee of Ksikes. Since 2006, Ksikes and Essaouni have maintained the monthly DabaTeatr Citoyen symposium, which features improvised scenes, circus, dance, and multimedia performance art. Today, Essaouni continues to direct DabaTeatr as a vehicle for the company’s devised texts as well as Ksikes work. For the second year in a row, the company is producing its ArtQaida festival to coincide with the anniversary of the February 20 Movement.

Many of DabaTeatr’s performances end up on the group’s YouTube page. Essaouni describes this project as an attempt to create a space for “citizen’s theatre.” Encouraging a mix of Morocco’s many spoken languages is a distinct part of that mission.

Digital Dissemination

Digital media also enables theatre groups to disseminate their performances through online outlets and even email list-serves. This has two major implications for these organizations. In creating their work, playwrights generally keep their target audience in mind—the public they envision will attend their performances and consume the content. Traditionally, audience members have been limited to those who are physically present at a performance. Now, however, writers can target people beyond their physical borders. In fact, DabaTeatr has actively sought out collaborators and audience members within the Moroccan diaspora; because of its active media presence, the group has also been able to partner with a number of German and French theatre companies.

But, digital media has been a double-edged sword for Moroccan arts. It has certainly reinvigorated parts of the performing arts scene by providing access to new audiences and funding sources. At the same time, though, it has created a situation wherein artists may find it more profitable—both in terms of fundraising and gathering cultural capital in the arts community—to seek out international audiences at the expense of local consumers.

Disseminating theatre scripts through digital media has also proven to be more difficult. Often these scripts are written using Latin characters and Arabic numerals, combining romance languages, Amazigh, and Arabic into one alphabet. While this allows a diverse array of people to enjoy these texts, it does not enable easy reproduction. On the other hand, this linguistic diversity gives artists the freedom to work without fear of censorship. It is no coincidence that foreign embassies and cultural institutions play a crucial role in funding these companies’ work. By seeking out financing from foreign institutions, theatre makers can be more subversive and need not worry about obtaining approval for their work from the Ministry of Culture.

Conclusion

It is clear that Moroccan Arabic language theatre is on the rise in Morocco. The emergence and persistence of artists, such as Ksikes, and groups like DabaTeatr, working with and in the tradition of, Feb20, demonstrates the movement’s potential long-term effects. An increase in improvisation, devised-texts, and multi-media performance has also served to re-energize a medium many veteran actors considered lost to television and film production. Through their emergence, these theater companies are providing a very real outlet for a new kind of public discourse in Morocco.

*George Bajalia is a staff writer for Muftah, cultural critic, theatre artist, and former Fulbright research grantee in Morocco. Follow his work at www.georgebajalia.com or on Twitter @ageorgeb.

An Interview with Riad Ismat on Art, Syria, & the Diaspora /

This article was originally published in Muftah.org and has been reprinted here with permission.

http://muftah.org/interview-riad-ismat-art-syria-diaspora/

Riad Ismat, Buffett Center Visiting Scholar at Northwestern University, is an award winning Syrian short-story writer and an acclaimed dramatist/critic in the Arab world, with 12 plays and 6 collections of stories and several books of criticism on arts and literature to his credit. He was Syrian minister of culture (October 2010 – June 2012), and also served as ambassador, director general of State Radio & TV, and Rector of the Academy of Dramatic Arts. He read English at Damascus University and completed graduate studies in theater direction at Cardiff University. He was trained as a television producer at the BBC, and was a Mime instructor with Adam Darius in London. Subsequently, he went to the United States as a Fulbright scholar, where he worked as an assistant to Joseph Chaikin, and wrote a dissertation on improvisation and theatre games in actor training. Ismat also directed extensively in Damascus, especially plays by Shakespeare and Williams, beside his versions of the Arabian Nights, Shahryar’s Nights, Sinbad and Game of Love & Revolution. He wrote In Search of Zenobia, Abla & Antar, Mata Hari and Was Dinner Good, my Sister, as well as a book on the Nobel prize laureate Naguib Mahfouz. He also wrote 7 television serials, broadcast from many Arab satellite stations, especially the award winning Holaco. In his career, Ismat has emphasized bridging the gap between cultures, drawing from Arab heritage with an experimental approach, advocating humanitarian values and condemning totalitarianism that represses freedom of expression, stressing democracy and tolerance.”

-Official Biography from Northwestern University

I recently had the pleasure to meet and get to know Professor Riad Ismat and hear about his work as a playwright, short story & script writer, and literary critic & theater director. His storied career both fascinated and impressed me. Of course, what stood out, initially, was his tenure as Syrian Minister of Culture from October 2010 until June 2012, when he requested to be relieved from his post in solidarity with the Syrian non-violence movement. After leaving this position, Dr. Ismat spent a year in Paris before arriving in Chicago as a visiting professor at Northwestern University. His work as an author and artist began long before this, however.

Dr. Ismat has graciously agreed to allow our conversations to be reproduced, in abridged version, here.

George Bajalia (GB:) Let’s start by talking about theater in the Middle East, in general. Often, we hear there is no history of Arabic theater, or that Islam somehow prohibits theater. That’s wrong though, isn’t it? Today, many academics and theater artists point to Egypt in the early 1900s as the birthplace of contemporary Arabic drama. Is that right?

Riad Ismat (RI:) It’s agreed among scholars that theater in the Middle East began in 1848 in Beirut by Marun Al-Naqqash. Soon after, it flourished in Damascus thanks to Sheikh Abu Khalil Al-Qabbani, who soon immigrated to Egypt. Because of its dominance in cinema, many believe Egypt also pioneered theater in the Arab world; but, historically speaking, theatre flourished first in the Levant region. Since the 1960s, there have been remarkable performing arts achievements in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Tunisia, Morocco, UAE and Qatar, as well as in Egypt. Nobody can deny, though, that in the first half of the 20th century, Cairo was an artistic hub in which Arab theatre ripened due to its significant distance from the dominance of the conservative Ottoman authorities.

In fact, there is no clear statement in the Quran that prohibits theater, because it did not exist in the pre-Islamic era for social and geographical reasons. For a time, misinterpretations by some fanatical members of the clergy led to banning performances that included women. Until today, in Saudi Arabia, only men are allowed to perform. Since the mid 20th century, the rest of the Middle East has enjoyed a varied quantity and quality of theater, with many male and female artists, who perform on stage, as well as in film and television.

GB: You have studied theater in quite a few different places – how have you seen theatrical trends develop over the past 20 years or so? Have you seen a particular influence in places like Damascus?

RI: There are some major differences between the “advanced world” and “developing countries”; they include disparities in resources and facilities, on addition to differences in the process of production in big theatre companies as well as in fringe theaters. In most of the Arab world, theater practice still relies on individual talent and effort, although there are government subsidies for national theater companies and experimental projects.

Regarding your other question, influences on Arab theater varied a lot during the last two decades, in general, and on Syrian theater, in particular. For instance, in the 1970s there was a strong influence from Brecht’s epic theater[1] and from documentary theatre [2] Absurdist theatre[3] also had an impact. In later phases, there was a strong tendency toward director’s theater[4]. In recent years, these influences have declined and given way to other tendencies, mostly group playwriting and production. In the last twenty years, there were parallel influences going on simultaneously; some trends in performance even came from Tunisia.

I believe playwrights dictate where theater is going. Unfortunately, playwriting is in decline in the Arab world as many good writers focus on television, instead of theater. The standard for stage plays have retreated and fewer good pieces have appeared.

GB: What about your work in Mime? Are there particular benefits of physical theater in places such as Syria, where there is often a disconnection between the written language and spoken dialect?

RI: I studied with the American Mime, Adam Darius, in the early 1980s in London and was also exposed to different training methods in French Illusionary Mime. I found this experience to contribute to the Stanislavski-based method of acting instruction I used with my students at the Syrian Academy of Dramatic Arts, years before I became its Rector (2000-2002). A mixture of psychological realism and corporal performance worked like magic for me when I directed several Shakespeare plays. In fact, the substance of my latest manuscript on actor training draws on this experience.

Your other question touches on a very sensitive issue. Syria insisted for too long on using standard Arabic in its national theaters, while commercial theater companies, mainly producing low-brow comedies, liberated themselves from this requirement, which created a gap between good theater and the general public. It took a long time until I was able to start dismantling this obstacle and adapt Western realistic plays to the spoken dialect in Syria. I directed some of these plays myself, including A Streetcar Named Desire, The Glass Menagerie, Spring Awakening, and Death & the Maiden. I did not, however, use the spoken dialect when I directed Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale and A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

I wrote some adaptations of Western plays in the spoken language for other directors, including All My Sons by Arthur Miller and Miss Julie by August Strindberg, but did not do this with Hamlet or Macbeth or with the verse plays of Pedro Calderón. The majority of my own plays are written in standard Arabic, because of their historical nature, especially my adaptations of The Arabian Nights.

GB: You’re not just a writer, but a politician and diplomat as well. Of course, those experiences have influenced your own work as an artist, but how has your artistic career influenced your political life?

RI: I am a dramatist and creative writer who tackles politics in his literary works, but I am not really a politician. I have, never in my life, joined a political party and I was always proud that I expressed my conscience freely. I did hold some official posts due to my professional career in arts and literature, and I admit I benefitted substantially from my experience in drama in my work as a diplomat and minister of culture; but these jobs did not influence my literary and artistic career much.

To elaborate on this point a bit more, in drama we have a high goal and vision, (you may call it “intention” or “dramatic action”). We also have a mission and, eventually, a “concept” so that we should know how to overcome obstacles (which you may call “beats” or “activities”.). If all this is applied to politics and diplomacy much would be achieved.

GB: With the so-called “Arab Spring,” many people are talking about the role of state media and independent media in generating public discourse. You are no longer affiliated with the Syrian government because of disagreements with the acts of Bashar al-Assad’s regime over the past few years. What role do you see film and theater playing in Syria over the next few years?

RI: I hardly see many truly independent media institutions in the Middle East, although some claim to be. Each is subsidized by one party or another. As a matter of principle, we have to realize that media is one thing and culture is another. My strong conviction is that culture exists to unify a nation, not to divide it. During my tenure as minister, I emphasized the role culture should play in promoting values of tolerance, diversity, pluralism, democracy, and freedom of expression.

On the other hand, it is the duty of any humanitarian writer or artist to disapprove of violence; therefore, I was against the so-called military/security solution, which was used instead of engaging in a political dialogue in response to the demands of demonstrators for tangible and quick reform. I thought it was the wrong choice to unleash the brutality of the intelligence apparatus based on a conviction that Syria is facing a foreign conspiracy. I grew up with conspiracy theories so there is nothing new in that. It resulted into counter violence. My advice was that such seeds would yield a poisonous harvest. In my view, regimes cannot engage in negotiations with an opposition considered to be a terrorist group. Any government must recognize the legitimacy of the opposition in order to start constructive dialogue that seeks a political solution through a compromise. It is a needed sacrifice in such hard times. Those extreme factions among the Syrian opposition do not represent the majority of the opposition. In fact, many of the artists and writers I met in the opposition believe in secularism, reform, and democracy, not in terrorism and dismantling the state.

Personally, I have a strong belief in what arts and literature can contribute to Syria’s future. If you wish to make predictions, you could examine what many plays, films, and television serials advocated in the last three or four decades. You will realize that, strangely enough, most of the creative work coming out of Syria was daring, although many were subsidized by the government. Writers and artists succeeded in one way or another in transcending censorship – a problem in Syria which the West overemphasized and overestimated – and transmitting independent criticism. They managed this through symbolism, allegory, and political projection. I myself relied on these techniques, in my plays The Game of Love & Revolution, Sinbad, Mourning Becomes Antigone, Was Dinner Good, dear Sister and In Search of Zenobia and, most certainly, in my new play. Chemical.

GB: Today’s art world is more transnational in some ways, but more limited in others. We’ve also seen a marked rise in art movements in the diaspora, especially by peoples from the Middle East and North Africa, who are searching for ways to articulate a shifting-sense of homeland. Has the focus of your work changed since you left Syria?

RI: Yes, there is a certain amount of truth in this. But I must confess that I do not know enough about Arab theater in the diaspora. Personally, I have been under the influence of being in exile over the last twenty months or so. In this period, I have written a play and a novel about the impact of the Syrian crisis, which is happening before the sight and hearing of the world, which is either misinterpreting or ignoring the unprecedented death toll and suffering. I think that by avoiding responsibility, many countries are encouraging the destruction of Syria and drawing it to a very dangerous abyss. I am not speaking out of nostalgia; everybody knows Syria enjoyed remarkable security before the violent suppression of dissent, which has led to the current civil war, ignited sectarian feelings and drove extremists from Sunni and Shiite sects to fill the vacuum and engage in an endless, absurd war on Syrian soil. The reluctance of the West to intervene politically has led to a big and painful human tragedy. Once upon a time, Syria was a rare secular example that prided itself on having many ethnic groups that co-existed together like pieces of a beautiful mosaic, but the violent crackdown against the revolution has led to armed conflict that has inflamed the whole country and now threatens repercussions on neighboring countries in the region.

GB: I am curious about your newest play, Chemical. The title seems to suggest a very contemporary, perhaps very political, element to this piece. You have been working on it since arriving in the United States. What prompted you to write this new piece?

RI: I realized that many people in the Western world are not aware of the nuances and complexities of the Syrian crisis; they only know the headline news through media. This motivated me to write Chemical in order to represent all facets and points of view about this devastating tragedy, which is unfolding in what was once one of the most peaceful and secure countries, turning it into hell.

*George Bajalia is a staff writer for Muftah, cultural critic, theatre artist, and former Fulbright research grantee in Morocco. Follow his work at www.georgebajalia.com or on on Twitter @ageorgeb.

[1] Brecht was chiefly reacting to the naturalism of artists such as Constanin Stanislavky and Anton Chekhov, who sought to depict the natural world in all its dramas and minutia. For Brecht, the epic theatre was built on a notion that the audience should be aware of its own relation to the performance and included more direct address, projection, and obvious illusion.

[2] Documentary theater refers to theater developed from extant texts such as newspapers, news and academic reports, and interviews. The well known piece The Laramie Projectchronicling the death of Matthew Sheppard in Wyoming is an example of documentary theatre. Documentary theater artists, for example Moises Kaufman and Anna Deavere Smith, often create their work with an explicit intent of advocating for social justice. Internationally, Peter Weiss is a notable artists in the field of documentary theater, and someone Dr. Ismat considers highly influential in his own work.

[3] Absurdist theatre, also known as the theatre of the absurd, refers to a theater trend emerged in Europe in the latter half of the 20th century. Theatre of the absurd depicts the existential, or purposeless, existence. Lyrical poetry, conversation, rampant diversions, and illogical situations replace traditional linguistic connotation and dramatic arch. Well known artists associated with this genre include Samuel Beckett, Václav Havel, Eugene Ionesco, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Harold Pinter, and Edward Albee.

[4] The phrase “director’s theater” refers to the shift in the role of a stage director. Instead of working on the literal directions and dialogue of the author – as was the traditional role of the stage director – some directors began adapting texts to fit alternate circumstances and time periods, or shifting texts into new dramatic genres. Critics of the movement argue that this can, and often does, occur at the expense writer’s original intention. Advocates argue that adapting text can actually better serve the author’s intention, and its original context, to contemporary audiences.

Whose Sahara? Morocco’s Nationalist Games /

This article was originally published in Muftah.org and has been reprinted here with permission.

http://muftah.org/whose-sahara-moroccos-nationalist-party-games/

George Bajalia, with contributions from Toshiro Baum

Over the past few months, a series of high profile events have refocused international attention on the territorial dispute between Algeria and Morocco over the Western Sahara. In a series of forthcoming articles, we will look at the historical trajectory and present implications of this dispute in the context of the domestic political economies of Morocco and Algeria and regional power dynamics in North Africa.

In this article, we focus primarily on Morocco. By outlining the country’s history with the Frente POLISARIO, the Western Sahara’s indigenous independence movement, as well as the domestic political factors shaping notions of Moroccan sovereignty and regional primacy, we provide context for understanding the kingdom’s position on the Western Sahara’s status.

Historical Roots of the “Sahara Issue”

Like many contemporary border disputes in North Africa, the conflict over the Western Sahara is rooted in colonial politics. In the 1970s, the Kingdom of Spain, which had controlled the territory since the late nineteenth century, partitioned its Sahara properties and ceded all authority to Morocco and Mauritania.